(For those who are multi-hull enthusiasts, it was a Piver design, a "first generation" tri. Bill had modified the hull with a skeg, but it was still a dog to windward, and I never saw her go more than six knots. We did, however, have it weighed down with considerable impedimenta, diving equipment, and canned goods.)

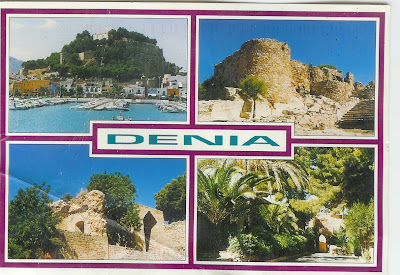

(For those who are multi-hull enthusiasts, it was a Piver design, a "first generation" tri. Bill had modified the hull with a skeg, but it was still a dog to windward, and I never saw her go more than six knots. We did, however, have it weighed down with considerable impedimenta, diving equipment, and canned goods.)After clearing customs we were directed to a new marina just north of the main city, San Miguel. Today it’s a bustling place with a population of at least 100,000 permanent residents. Back then it was still basically a sleepy little village. It was easier to sense some of the history and culture of the place without all the modern-day annoying glitz that we call progress.

There were maybe a dozen other boats in the marina. There was a couple other cruisers like us, some Mexican sport and commercial fishing boats. There was one huge motor-sailing yacht called the Sea Wolf. The Sea Wolf was about 100 feet in length, and seemed to be well appointed--mahogany rails, teak decks, a couple of Boston Whalers on davits. We were puzzled that, although she was docked, there seemed to be one engine running all the time.

After a few days of exploring the island, the gang decided to take the trimaran to a reef at the north end of the island to fish and dive for a few days. Another friend was tentatively scheduled to fly in and join us, so I told them to go ahead without me. I would be there in case she arrived.

The next morning, a Sunday, I went into town to a larga distancia to see if I could find out if she was still going to make it.

As I was waiting for my call to be put through, an affable man in his fifties approached me. "Excuse me, would you know what time it is in Miami?" he said. I knew it should have been an hour earlier, but I also knew that Mexico had a different scheme for daylight-saving time than we did, so I told him I wasn’t sure.

"Gee, then that’s a problem," he said. "Because if I call too early, you see, all my friends will be in church."

He spoke with a Midwestern accent, and seemed like a wholesome, energetic fellow. I pictured nice middle-aged couples going into a nice little church fringed with palm trees.

"Yes, I’m afraid all my friends will be in church." He looked at me, and as an afterthought said, "My name’s Al Lefferdink, by the way." We shook hands, and I introduced myself, and explained that we were on a boat at the marina, but that I was staying in town for a couple of days while the others went fishing.

"Oh, that’s great," he said. "We’re in the marina, too. Maybe you’ve seen my boat–the Sea Wolf?" Yes, it would be hard to miss it. "Well, actually I’m in a bit of a jam. Maybe you could help me out," he said. He explained that he’d lost his crew due to a misunderstanding. At the same time there was a possibility that the Mexican authorities had placed a lien on his yacht. For this reason he wanted to have an American citizen on board, just to keep an eye on things. He had to fly out that day on business, and would be back in a few days. Would I be willing to stay on board until he got back? I figured, "Perfect! This way I can stay right at the marina!"

He introduced me to a couple of Mexicans with whom he had been doing business, and gave me the names of a couple more that could be expected to visit, including the Port Captain. I got a few things from the trimaran, and moved on board, telling my friends where I would be staying, and as much of the situation that I knew. Mr. Lefferdink told me that he had the engine running because the ship’s generator was down. It was now off. The other systems on the ship, like the water pumps, weren’t working either. Apparently the ship’s engineer had disabled most of the systems before leaving, his own way of leaving an invoice for monies owed. It would be a little like camping.

Our trimaran pulled out of the marina. Lefferdink left his final instructions, and headed toward the airport in his rented Volkswagen Thing. I shut the mahogany gate on the ship’s rail, and observed the splendid surroundings of the luxurious yacht. I was now master of the Sea Wolf.

My smugness lasted until sundown. The ship had no power, and it was getting dark. I tried to read with a flashlight, but the only books I had were one I had brought with me, Spanish for Beginners, and one that Mr. Lefferdink had recommended, a paperback called Lansky.

I unrolled my sleeping bag on a comfortable settee in the ship’s main salon. Mexico’s a poor country, and this was an expensive mega-yacht. It seemed to be attracting a great deal of attention. As I closed up the cabin for the night, for example, I noticed that there still seemed to be people watching the boat from a rise over the marina. But it was pitch dark out. Didn’t they ever go home?

The fun was about to begin.

After they were gone, someone put up a big sign at the corner that said, "The Crack House is Gone: Smile for the Camera!" It didn’t last long. The "rental agent" tore it down in a fit of rage. We sometimes wonder if the sign had gone up six months earlier, we could have saved everyone a lot of trouble.

After they were gone, someone put up a big sign at the corner that said, "The Crack House is Gone: Smile for the Camera!" It didn’t last long. The "rental agent" tore it down in a fit of rage. We sometimes wonder if the sign had gone up six months earlier, we could have saved everyone a lot of trouble.